Icons, shrines, and Anglicanism

Iconoclasm, the destruction of images of Christ, the Virgin, or the Saints, stems from an insufficient appreciation of the full humanity of Christ, and as such it is a heresy. The creation of specific imagery of Christ and other Christian figures did not become prevalent until after the waning of paganism. Iconoclasm was most prevalent during these introductions; by the 8th Century a great deal of superstition had arisen in connection with the images and the debate concerning their use had become contentious (Moss, The Christian Faith, 1957, p 88). Saint John of Damascus clarified the issue of images as it related to Christology, stressing the reality of Christ’s humanity. The Second Council of Nicea in A.D. 787 condemned the iconoclasts and directed pictures be restored to the churches.

Churches north of the Alps not represented at Nicea II rejected the decrees of the council. The Council of Frankfort declared that pictures could be used in churches, but not worshipped (misunderstanding the nuances of Nicea II between "veneration" and "adoration" or worship). The authority of Nicea II was questioned by the theologians of the western Church as late as 1540. The Protestant Reformation ignited a new wave of iconoclasm in the West, especially in the churches of the Puritan, Presbyterian, and Reformed traditions. Iconoclasm did not affect Lutheranism to a great degree—crucifixes, statues, and paintings have been in continuous use in Lutheran worship since the Reformation.

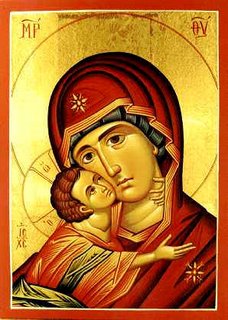

Anglicans had varying views on the subject. The cross and candles upon the Altar were often retained by the high churchmen (for instance, Queen Elizabeth I kept an ornate crucifix in her chapel). Post-Reformation portraiture of Anglican divines such as Cranmer, Andrewes, and Laud demonstrated the development of a type of “Anglican iconography,” as did the continued practice of creating effigies for the monuments of the deceased prelates in English Cathedrals. During the Puritan Commonwealth much ancient Christian art left in place in England at the Anglican Reformation was thoughtlessly defaced (literally—it means to destroy the faces) or otherwise destroyed. Anglo-Catholic churches (from the late 1800s to the present) have brought back the crucifix, icons, and statues of Saints to Anglican places of worship, but the iconographic structure and organization of the images as found in the Eastern churches is often lacking. Indeed, in many parishes proportion and focus are lost amid a sea of statuary and images and a repetition of the crucifix.

While God the Father cannot be pictorially represented (He is never depicted in the icons of the Eastern Church, although He often is in the West—as an elderly mirror image of Christ; this is indeed an example of bad theology), both the Holy Ghost and Christ have been depicted in Eastern iconography, the Spirit as a dove or a tongue of fire, both images with biblical foundations. As Christ was Incarnate and fully assumed our human nature, it is not incorrect that His image can be likened as best we can assume He appeared in the flesh. Honor (veneration) paid to such an image is not to the wood or paint, but to the Person of Christ (just the same as when we bow in the Liturgy at the Name of Jesus, we bow not to vibrations in the air, but to the Incarnate Word). The ability to depict Christ as man, as Incarnate God, speaks to the truth of Christianity—we don’t just worship some unseen Deity. Even though we cannot imagine the glory of God the Father nor create any likeness of Him, we have the human attestation of His nature in the Person of Christ.

I have a Methodist relative (I come from that tradition myself and have a bust of John Wesley on my desk) and she has a picture of Jesus (normal European depiction: flowing blond hair, pale skin, blue eyes) in her bedroom. When I visited her house some time back she mentioned, looking at the picture, that she talks to Him every day. I knew what she meant, as would almost any other Christian. Nobody would think that she spoke to the picture or thought that it had any special power. She had an implicit theory of Christian iconography. She speaks not to the image, but to the One that it represents.

As Christ was Incarnate, we can depict Him and revere His image and likeness. As the Saints were humans, we can do likewise. We cannot think that the images have any value or power in and of themselves. They are not magic. I believe most protestants have an understanding of icons close to the understanding of the Second Council of Nicea, even though they might abhor or question their use in Lutheran, Orthodox, Anglican or Roman Catholic worship. Pictures of Christ (or even the Holy Family, if it is Christmas time) might be set upon the mantle and treated with respect in Christian homes of many traditions. If someone were to come into the home and spit upon the image of Christ or smash the crèche the person would probably be horrified, because they would rightly interpret the attack upon the image as an attack on the idea of Christianity or the person of Jesus. If a Democrat has a picture of Kennedy on the wall or the Republican a picture of Reagan and a visitor looks at the image and expresses pleasure or disdain, almost everyone knows that the displeasure or appreciation is directed at the person, not at the image.

The Affirmation of Saint Louis embraces the Seven Ecumenical Councils without qualification. The Constitution and Canons of the Reformed Episcopal Church states: “Nicea II (787). . .is disputed in respect of its ecumenicity and application, though in principle its condemnation of Iconoclasm is conceded to be orthodox.” Therefore, the bulk of classical Anglicanism embraces the theology of Nicea II. The main questions that remain for many classical Anglicans pertain not to the general theological conclusions of Nicea II, but rather to the wording of many of the directives within the pronouncements of the Council. The canons resulting from this council do not just allow for images in places of worship, but direct that images be placed in all churches and that honor be paid to these images through gestures (bowing, kissing, etc), and that those who reject “all ecclesiastical tradition, whether written or non-written” be condemned (something that would have to be reconciled to the Articles and their affirmation that nothing is required than that which can be proven by Holy Scripture). An Anglican service of the Holy Eucharist can be validly celebrated without a cross upon the Holy Table; an Orthodox liturgy (to the best of my knowledge) demands the use of an icon. It is in these regards that many Anglicans still question the “ecumenicity and application” of the council, while readily admitting that its Christology in defense of Christian art and its use is orthodox. If any Anglican you speak with says otherwise, ask him if he has a Nativity set or has sent a Christmas card with the Virgin and Child upon it.

Relics and Pilgrimages

Every year or so I go to a large shrine that houses the mortal remains, the relics, of a man beloved by millions--the shrine is huge and impressive, filled with icons of the man entombed there. There are paintings, busts, and in a museum nearby numerous wax figures. It is the shrine of the 16th president of the United States. Usually I will take a token of my pilgrimage back with me; last time it was a bust of President Lincoln. With this example we see that most people will embark on some manner of pilgrimage in their lives to visit the tomb of a famous person now deceased, even if it is a secular one. All of us visit the graves of those we have loved and lost. Even the most ardent Protestant must admit the similarity between the two practices.

Wheaton College in Illinois has a collection of the "relics" of C.S. Lewis (personal belongings, etc) and many Christians have made pilgrimages to see them. However, there are no indulgences granted for such trips, and no years will be taken off of time to be spent in purgatory. What such pilgrimages will do is help to connect the living with the faithful who have "departed this life in Thy faith and fear" that "we might follow in their good examples."

There should be no objection to pilgramages to such shrines, either to C.S. Lewis or to Lancelot Andrewes, or to the site of Cranmer or Laud's martyrdom. What most find abhorent (as the Reformers did in the late Middle Ages) is the creation and selling of relics--body parts taken from the grave, dismembered portions from a desecrated corpse removed from his resting place in Christian burial and sold for profit. There is a great and important difference between visiting the tomb of a faithful Christian and taking parts from that faithful Christian in order to create "a tomb away from the grave." We must ask ourselves if we would approve of the dismemberment of a saintly elder of our family so that a church might have "a piece of her" for the parish. . .I would hope not.